Neotameme

Escultura y acción performática, Ciudad de México, 2021

ESP

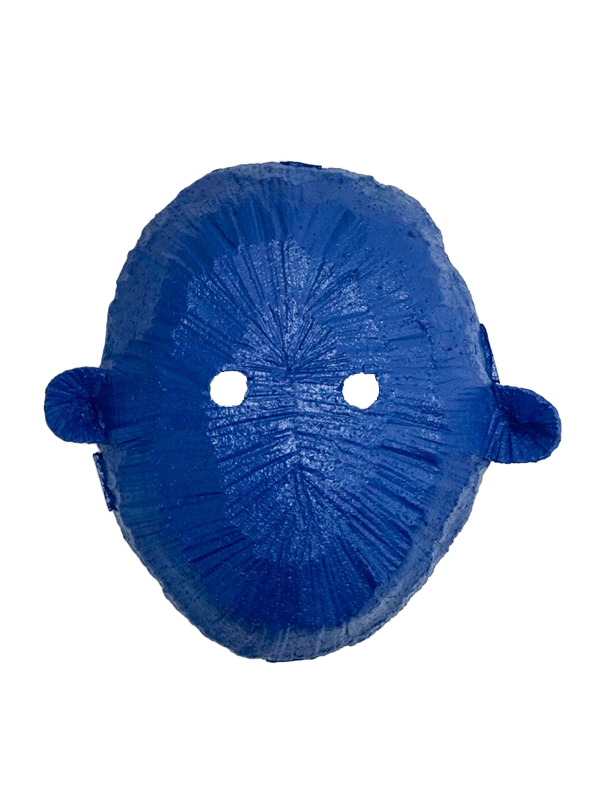

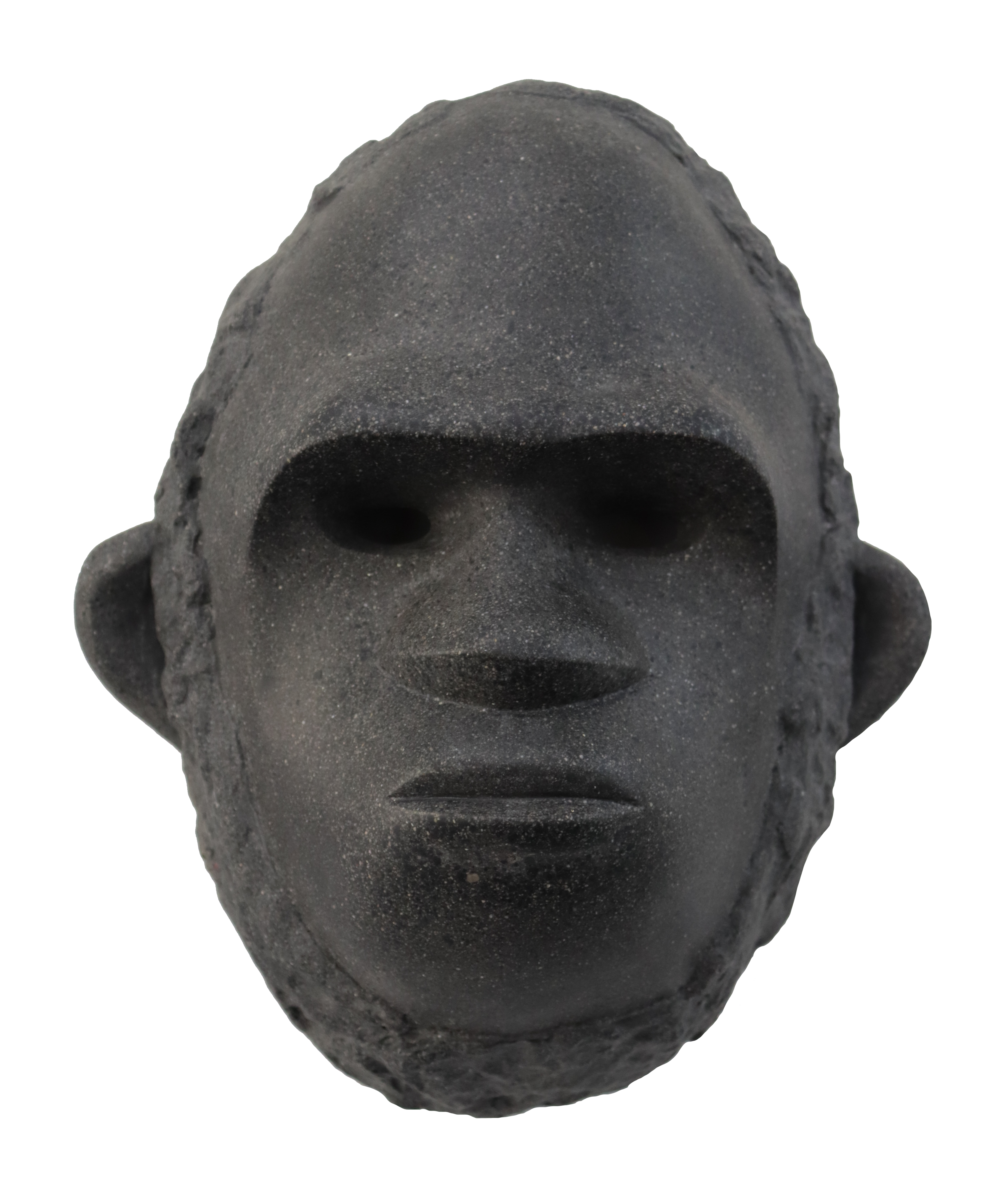

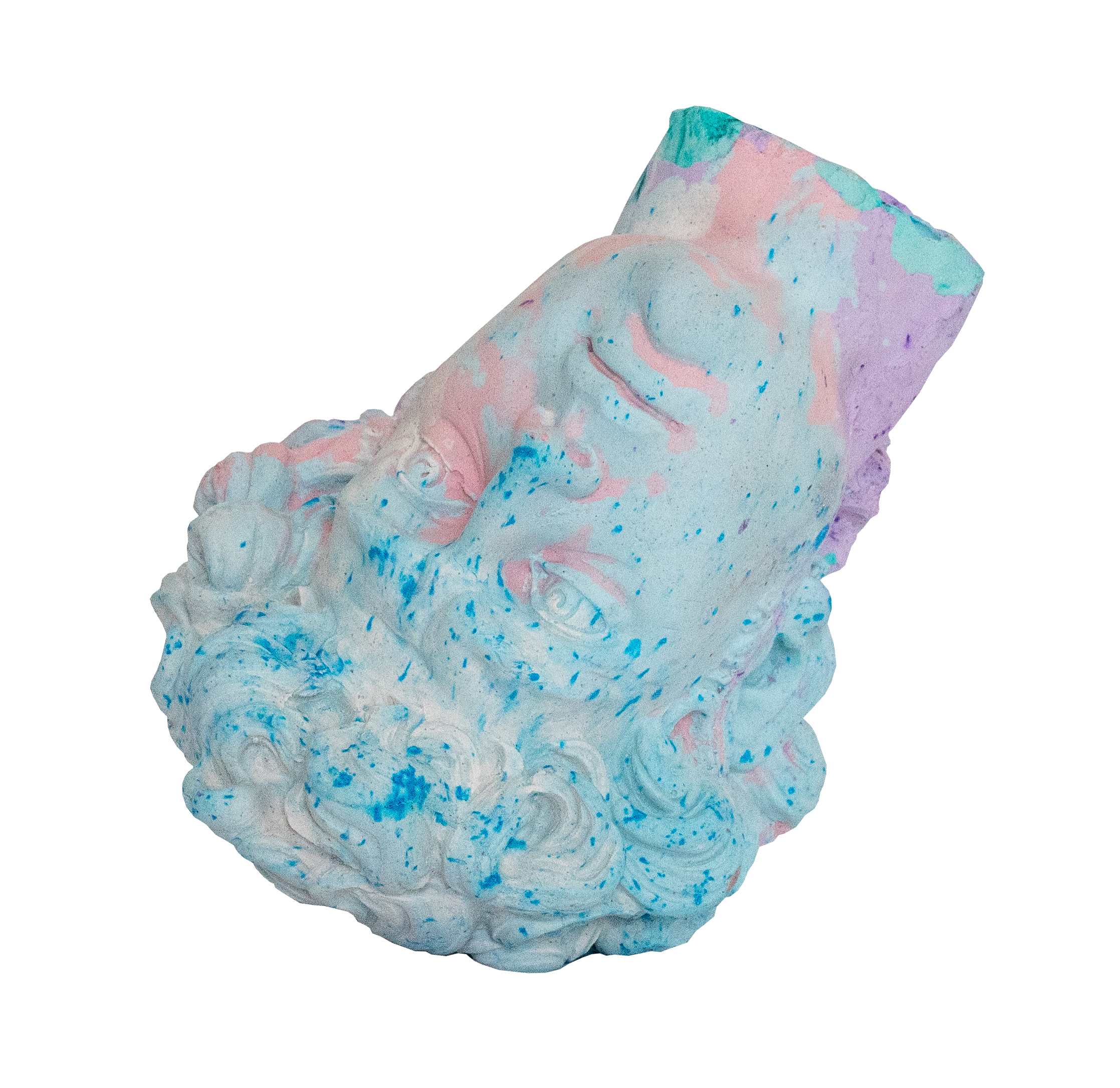

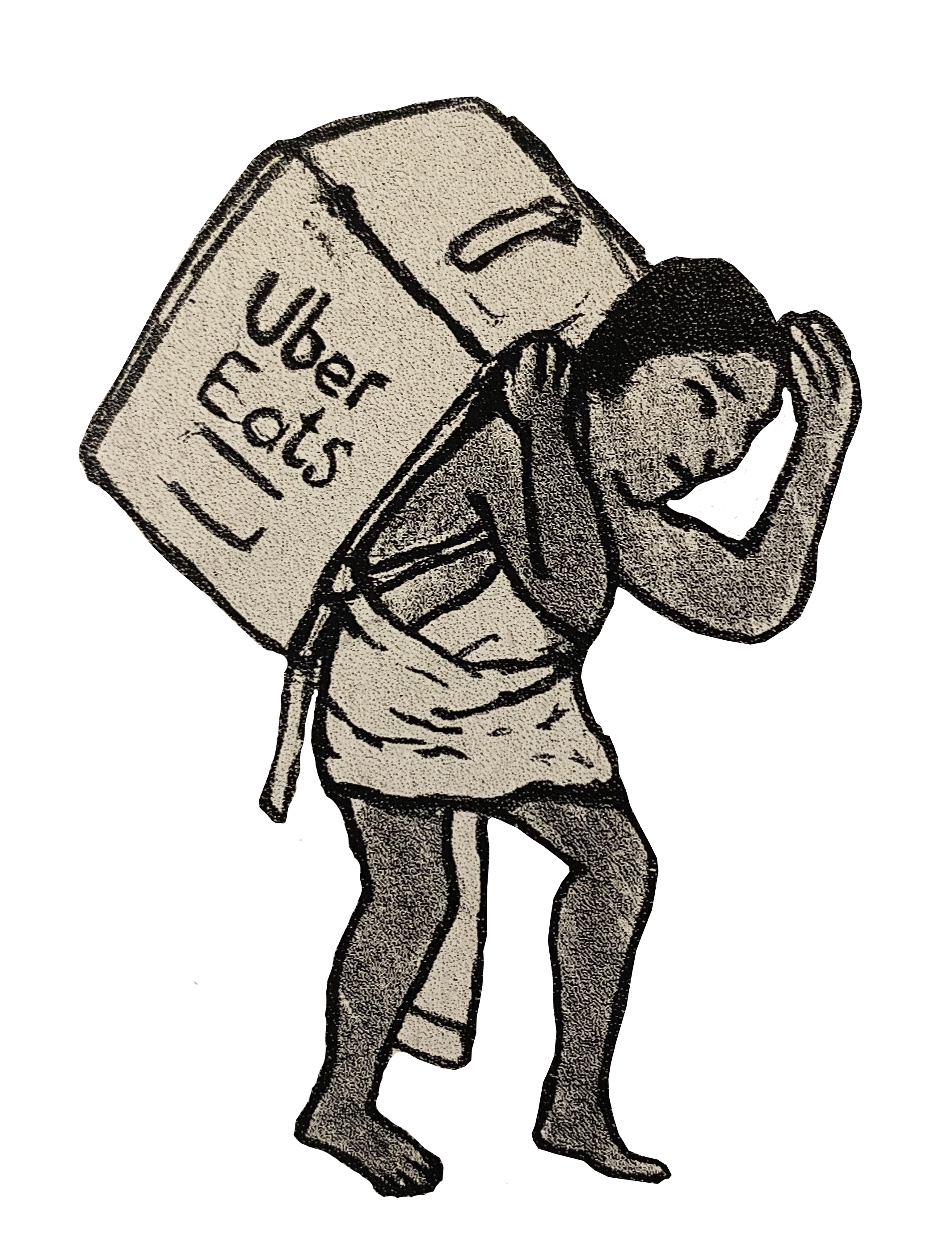

Del náhuatl tlamama = cargar, el tameme fue para los pueblos nahua-mexica la persona encargada de trasladar, sobre su espalda, mercancía de un lugar a otro. En Neo-tameme (2021), a través de la acción performática de hacer delivery de alimentos portando una mochila-cabeza olmeca, Chavis Mármol buscó reinterpretar este personaje y sus connotaciones en la contemporaneidad de la Ciudad de México.

Las cabezas colosales de la civilización Olmeca tienen, a pesar de su enorme tamaño y peso, una larga historia de desplazamientos: durante el período prehispánico, sin que se conozca el motivo o los medios, fueron trasladadas a grandes distancias de sus lugares de producción; desde su “descubrimiento” a principios del siglo XIX, varias de ellas fueron emplazadas en museos que, además de velar por su conservación, colaboraron en la construcción de un relato identitario que traza una línea directa entre las grandes civilizaciones mesoamericanas y el México moderno; a fines de siglo, transformadas en embajadoras oficiales del mexicanismo, viajaron en representación de México a diferentes capitales del “primer mundo” con ocasión de importantes exhibiciones y ferias internacionales. Durante la pandemia, Chavis, montado sobre una bicicleta y ejerciendo la precaria labor de repartidor de uber eats, desplaza este símbolo por las calles de la Ciudad de México.

Así, tanto por su materialidad farsante como por su función de uso profana, esta escultura performática abre discusiones entorno al uso político y comercial que se da al patrimonio desde las estructuras de poder por un lado y, por otro lado, a las posibilidades de apropiación lúdica y desacralización de este patrimonio y de lo que representa

ENG

From the Nahuatl word "tlamama," meaning "to carry," the tameme was the person in charge of transporting goods from one place to another on their back for the Nahua-Mexica peoples. In Neo-tameme (2021), through the performative action of delivering food while carrying an Olmec head backpack, Chavis Mármol sought to reinterpret this character and its connotations in the contemporary context of Mexico City.

Despite their enormous size and weight, the colossal heads of the Olmec civilization have a long history of displacement: during the pre-Hispanic period, for unknown reasons or means, they were transported great distances from their places of production; since their "discovery" in the early 19th century, several of them were placed in museums that not only ensured their preservation but also collaborated in the construction of an identity narrative that draws a direct line between the great Mesoamerican civilizations and modern Mexico; by the end of the century, transformed into official ambassadors of Mexican identity, they traveled on behalf of Mexico to different capitals of the "first world" for important exhibitions and international fairs. During the pandemic, Chavis, mounted on a bicycle and performing the precarious work of an Uber Eats delivery person, moves this symbol through the streets of Mexico City.

Thus, both for its counterfeit materiality and its profane use, this performative sculpture opens discussions about the political and commercial use given to heritage by structures of power on one hand, and on the other hand, the possibilities of playful appropriation and desacralization of this heritage and what it represents.

Escultura y acción performática, Ciudad de México, 2021

ESP

Del náhuatl tlamama = cargar, el tameme fue para los pueblos nahua-mexica la persona encargada de trasladar, sobre su espalda, mercancía de un lugar a otro. En Neo-tameme (2021), a través de la acción performática de hacer delivery de alimentos portando una mochila-cabeza olmeca, Chavis Mármol buscó reinterpretar este personaje y sus connotaciones en la contemporaneidad de la Ciudad de México.

Las cabezas colosales de la civilización Olmeca tienen, a pesar de su enorme tamaño y peso, una larga historia de desplazamientos: durante el período prehispánico, sin que se conozca el motivo o los medios, fueron trasladadas a grandes distancias de sus lugares de producción; desde su “descubrimiento” a principios del siglo XIX, varias de ellas fueron emplazadas en museos que, además de velar por su conservación, colaboraron en la construcción de un relato identitario que traza una línea directa entre las grandes civilizaciones mesoamericanas y el México moderno; a fines de siglo, transformadas en embajadoras oficiales del mexicanismo, viajaron en representación de México a diferentes capitales del “primer mundo” con ocasión de importantes exhibiciones y ferias internacionales. Durante la pandemia, Chavis, montado sobre una bicicleta y ejerciendo la precaria labor de repartidor de uber eats, desplaza este símbolo por las calles de la Ciudad de México.

Así, tanto por su materialidad farsante como por su función de uso profana, esta escultura performática abre discusiones entorno al uso político y comercial que se da al patrimonio desde las estructuras de poder por un lado y, por otro lado, a las posibilidades de apropiación lúdica y desacralización de este patrimonio y de lo que representa

ENG

From the Nahuatl word "tlamama," meaning "to carry," the tameme was the person in charge of transporting goods from one place to another on their back for the Nahua-Mexica peoples. In Neo-tameme (2021), through the performative action of delivering food while carrying an Olmec head backpack, Chavis Mármol sought to reinterpret this character and its connotations in the contemporary context of Mexico City.

Despite their enormous size and weight, the colossal heads of the Olmec civilization have a long history of displacement: during the pre-Hispanic period, for unknown reasons or means, they were transported great distances from their places of production; since their "discovery" in the early 19th century, several of them were placed in museums that not only ensured their preservation but also collaborated in the construction of an identity narrative that draws a direct line between the great Mesoamerican civilizations and modern Mexico; by the end of the century, transformed into official ambassadors of Mexican identity, they traveled on behalf of Mexico to different capitals of the "first world" for important exhibitions and international fairs. During the pandemic, Chavis, mounted on a bicycle and performing the precarious work of an Uber Eats delivery person, moves this symbol through the streets of Mexico City.

Thus, both for its counterfeit materiality and its profane use, this performative sculpture opens discussions about the political and commercial use given to heritage by structures of power on one hand, and on the other hand, the possibilities of playful appropriation and desacralization of this heritage and what it represents.